The Flyer

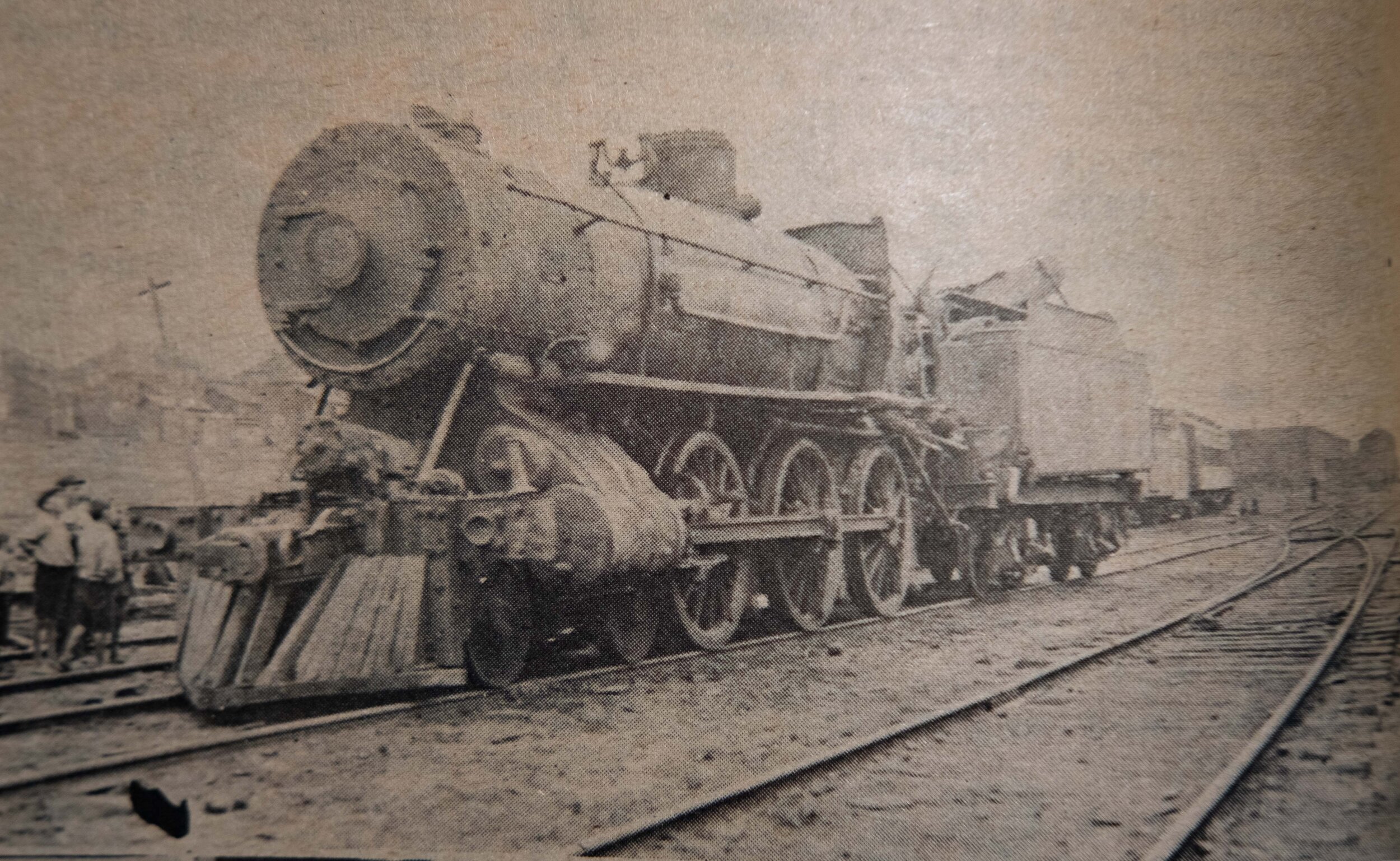

The most notable locomotive in the coal mining era was The Judique Flyer. Not only was it an economic means of shipping coal, but it also connected isolated Inverness to the outside world. This is the Flyer’s story…

Origins

The primary reason for the train was to serve the coal mines. According to History of Inverness County, the line was begun by William Penn Hussey in the late 1880s, as part of his Broad Cove Coal Co. The train carried coal to the pier at Port Hastings, and men served as trimmers as the coal was loaded aboard vessels. Eventually, the trains would serve as passenger transportation, which led to Inverness being more accessible to the rest of the province.

The Judique Flyer was an important means for social and economic activity, which brought people from all walks of life together. Waiting at the station for the incoming trains was an opportunity to exchange views, play a game of cards and make long-lasting friendships. Teenagers, in the 1920s and ‘30s, waited with anticipation for the weekend wait for the trains in the wee hours of the morning. Economic activity flourished with the coming of The Flyer. It was a vehicle by which produce was brought to market. Up to ten to fifteen cans of cream were brought to market every Tuesday and Friday.

Life on The Flyer was characterized by hard work, adventure, excitement and good times. Men who worked on The Flyer knew and accepted the hardships of their profession. Lacking proper equipment of the modern age, these men used their intellect, practical wisdom and bare hands to overcome barriers. The Flyer was usually equipped with a staff composed of an engineer, a brakeman, fireman, conductor and section man. One can only imagine how dangerous this job was when one considers the fact that these men worked regardless of weather conditions. they worked in blizzards, torrential rainfalls, and below-freezing temperatures.

The inside of the trains was composed of large, comfortable seats. On either side of the coach was a potbelly stove fuelled by coal that smoked if improperly stoked. The common consensus of the people who rode the train was that it rattled, shook, and moved from side to side on its journey down the tracks at a slow 20 mph. The Judique Flyer was a symbol of an age when the quality and character of the society was a closeness to a neighbour and community when individuals joined in celebrating their achievements and when life moved at a pace that could be enjoyed with a sense of fulfilment.

The Crew

In a 1978 interview with Hughie Dan MacIsaac, Gussy Carmichael and other Inverness County railway workers for The Cape Breton Magazine, the topic of the widely known locomotive, The Judique Flyer, is discussed in fascinating and personal detail:

Gussy Campbell: They called this train the “Judique Flyer.” Why it got that name I can’t tell you. Judique was noted for rough men, and they got their fame in Gloucester and all those fishing countries for scrapping and getting into rackets — fame for being powerful men, though I don’t think they were better than anyone else. But they got the name, the Judiquers. And I guess that’s why the train was christened the “Judique Flyer.”

Here we have just the one mainline from Port Hastings to Inverness, with sidings here and there. But listen, you can’t believe it. In the ‘forties, now, coming home at night, Judique Station was pretty much like Truro is today. You couldn’t move a round there with horses and wagons and the platform loaded, people coming to meet the ones coming on the train.

Hughie Dan MacIssac: Same thing here in Creignish. Crowd of young fellows gathering around mail time, train time. Many more people around then than there are today.

Gussy: The mines were going. The farmers had to get their products to the market. You take now at that time at every station there’d be 10 to 12 to 15 cans of cream. That went Tuesday and Friday. Then they were chipping calves away from here.

Hughie Dan: And there were oil cars on the trains, hauling in oil for the public — gasoline and all that.

Gussy: Then there’d be so much pit timber shipped. The pit timber was what the country fellows did. So much of the pit timber went to Sydney to the Dominion Coal Company. Some more went for the mine in Inverness. And we’d be down there in the ‘forties with our loads on the sleighs, waiting to see if the cars were going to come in for the lumber. And you’d be fighting for a car at the time.

Hughie Dan: Men did it all the way down the line till you got to Inverness. Well, they worked the mines.

Gussy: And then you waited for your returns. And you went to the store and you purchased your groceries on credit till the returns came for the pit timber. And very seldom you got money for it.

And then there were passengers. At that time there was no way of travelling, only by buggy -- so the train was an awful improvement. Sometimes I’ve seen them with 5 & 6 coaches on here, when I was a kid. And them loaded. You ought to be here Christmas Eve when the fellows would come with their loads of liquor. They went to Hawkesbury to get their booze for Christmas. Coming off and fighting and everything else. That wasn’t so hellish long ago.

Hughie Dan: That passenger train, she left Inverness in the morning about 7 o’clock and she went through on a timetable -- and she stopped at every station and she was dead on time.

Gussy: But at the last of it, it did take hours and hours to go from Inverness to Port Hastings. But not at first. You could set by it. We used to ship cream to the creamery at Port Hawksbury, and you had to be there at the station quarter to 8 or the train was gone.

(Were there any wrecks?)

Hughie Dan: There were a lot of train wrecks.

Gussy: She’d just go off the track. The worst wreck that I think was here was the time that Philpott was killed. The one at Judique Harbour. There was a washout. They were coming up and he was a strange driver on the road -- he wasn’t used to this road -- the old drivers would know where the bad spots were. But this was after an awful storm and he came along and didn't expect a washout and he plunged right into it. And the train toppled over on her side and it was a steam engine and he was scald to death.

Hughie Dan: It was between Christmas and New Year’s, in the ‘forties. I think it was Frank Philpott. Alex MacKinnon could tell you about that. I think this fellow was replacing him during the holidays.

Pictured: Hughie Dan MacIsaac & Gussy Carmichael

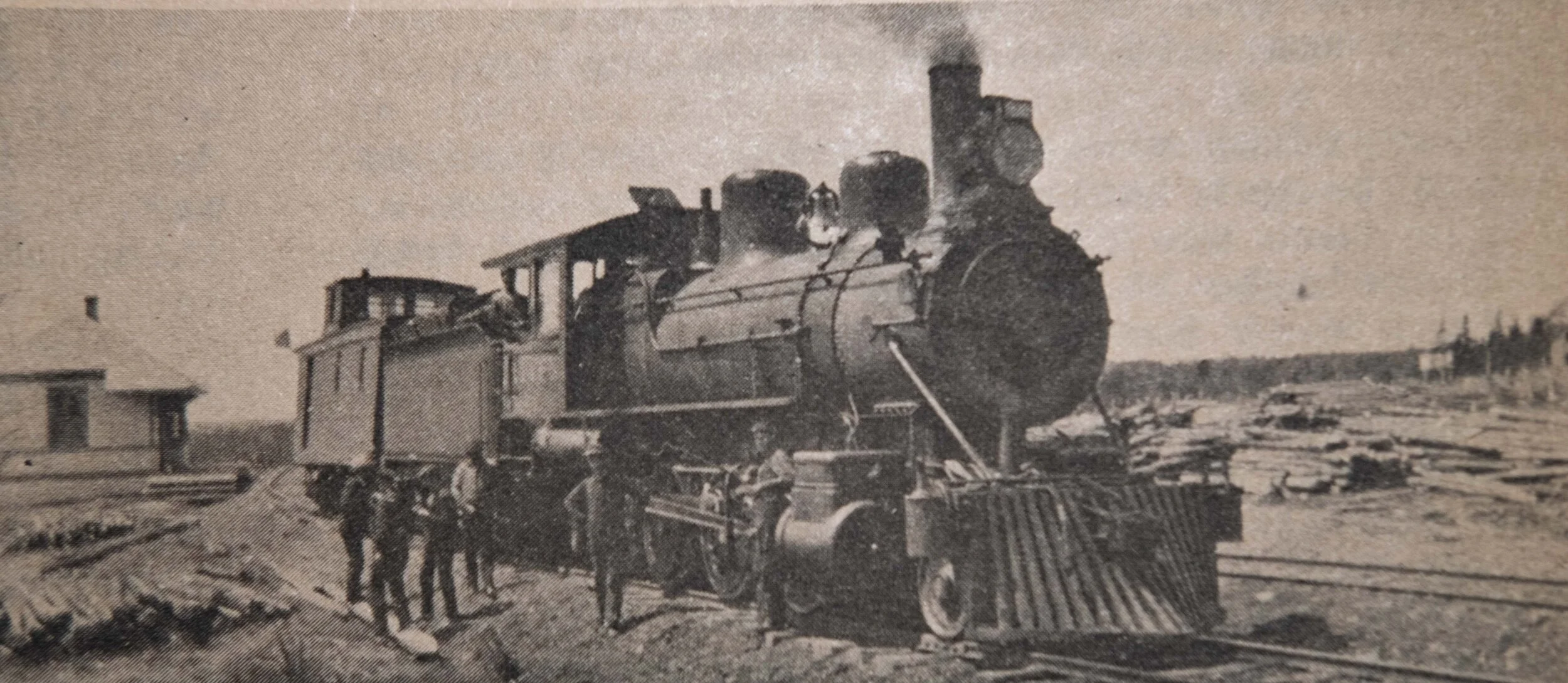

Alex MacKinnon, Engineer: My father was the first driver that ever took an engine over the I&R road. He came to Cape Breton when they were building the railroad, with a company called MacKenzie & Mann. He ran a shovel and he ran an engine both. That was in 1899. His name was James MacKinnon. So he married here and he stayed here, at Inverness -- and then he bought a home here in Port Hastings. A shunter job opened, looking after all the freight between Inverness Junction and Point Tupper.

(Your father taught you to be a driver?)

Yes. But all the fellows that I fired for on the I&R, if you wanted to know anything you asked then -- and they knew an engine because they had to do most of their own repair work. I became a driver in 1934. There wasn’t a special school. You studied it and they took you in and questioned you on different parts of the engine, air brake and all that.

(Were there ever people struck by the train?)

Oh yeah. I killed two. We had gone to Inverness with the plow. And we were hauling a freight of coal, coming back. So when we called, coming into Glencoe -- we had a cold day anyway and I had the window shut. So this little fellow was standing alongside the track, but he had his head down. So I waved. He had a black and white plaid jacket on. So he never picked his head up. I opened the window and looked back and I didnt see him. All I saw was two rubber boots. So I stopped right off the bat and I said to the fireman, fellow by the name of John Dan MacLean was firing for me -- “I think we got old Cameron.” So we got off the engine, went back. It was another fellow. He was under the engine -- back about third or fourth car.

Now where he was standing, the two rubber boots were still standing right there.

Right together.

You couldn't place them any better alongside the tracks.

Hughie Dan MacIssac: I think it was the automobile that was the killer of the passenger train.

Gussy Campbell: I really think the first decline of the thing was when they took the mails off. That was in 1954 -- and she started going down then.

Hughie Dan: Instead of a passenger train, they had a jitney on here for awhile too. Just one car for passengers. It was not up-to-date.

Gussy: Then they gradually started cutting out the stations. Now there’s no stations at all.

Not even in Inverness.

Funny Stories

Life on the railroad was not all doom and gloom. There were humorous times, as well. There have been many funny stories told of the famous device for catching cows. This cowcatcher was placed in front of the train. Cows roamed wherever there was grass, even if that grass was near or between the railway ties. Usually, these stubborn cows refused to move off the tracks with the sounding of the train whistle. Cows or no cows, The Flyer kept to its schedule.

A local resident, John Murdoch MacKinnon, of Kenloch, reflected on the first time the train passed by his home in 1901. “ I had my barn near the tracks and the horses were grazing. Once the train came the horses would go away the hell in the woods. I remember that well. Once I got them back in the barn, the damn train would come back and the horses took off again in the woods, They stayed there ‘til my father came back.”

Flyer’s Song

Progress was responsible for the disappearance of the Judique Flyer. In the 1950s, the 20-mph diesel quickly replaced the 20 mph steam trains. Mr. Stanley Collins of Lake Ainslie composed a song commemorating The Flyer’s glorious days, mystic nature and awe it inspired among the people of the small villages it passed. He stated, “I did then, and still do, miss her lonesome sounding whistle across the waters of Lake Ainslie. I thought I should jot down some verses lest we forget the Judique Flyer.”

Oh here comes the old black beauty

With her engineer on duty.

She is sure a rolling cutie

On the old Inverness line.

Chorus:

If it’s speed you desire

Climb aboard the Judique Flyer

There’s no need for other hire

For she’ll take you in on time.

Watch her roll; my what vision

There’s no danger of collision

Travelling to fulfil her mission

Running on a perfect line.

Sitting mid splendour beaming,

Soft fluorescent lights a gleaming.

Travelling with mo careening

‘Tis a feeling, oh, so fine.

Ladies fair, heed my story.

Generated winds of fury

From her speeding is her glory

May send dresses flying high.